Fred Holland Day

February 1882

South Station, Boston

If seventeen year-old Fred Holland Day (1864-1933) had a hero in this world, it was Oscar Wilde. They both loved the poetry of John Keats, whose early death heightened the romance of his work. They both believed in beauty for its own sake and that art needed no moralistic message or advanced artistic technique to justify it. And both were enthralled by the male form. How was Fred to know that on a wintry Boston afternoon in February 1882, he would meet his idol in South Station? Casting himself in the third person, Day wrote about the chance meeting ten years later:

“…he approached the Unapproachable, and …requested the Sun’s God his autograph. The Great One looked down upon the youth with that sunny smile so often and cruelly maligned as ‘incubating,’ and taking the pencil, slowly traced his name in calligraphy rather more curious than his appearance. The gates swung open and the throng (along with Wilde) passed through.”

Wilde was in Boston to give a talk. His reputation for delivering insults wrapped in literary velvet had preceded him. But this time the joke was on Wilde. On that winter evening, 60 Harvard students came to hear him speak at the Music Hall on Winter Street (now the Orpheum) in downtown Boston. The Lowell Daily Courier reported that “all were in knee-breeches and black stockings.” Each carried a sunflower and affected a far-off gaze. They were mocking Wilde and he knew it. The Harvard Crimson reported that at one point, Wilde glared at them saying, “Save me from my disciples.”

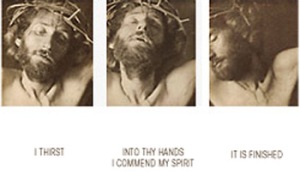

Day plays the role of Christ in The Last Three Words

Just ten years after the chance meeting in South Station, Day would sit in Wilde’s London study, tea cup in hand, not as a nervous acolyte but an equal. He’d become a leading book publisher, collector, and art photographer. He was well-known in art circles on both sides of the Atlantic. Day’s rise was fast but his most productive years were no more than a decade (1895-1905).

In recent years, Day’s reputation has improved but only after decades of silence among art historians. Why did this seminal figure in art photography and book publishing, sink into obscurity for so long? Another question suggested but never answered in Day’s biographies since his death: was he gay? Just who was this artist, obscured by time yet central to the history of photography?

Author Estelle Jussim has called Day “a slave to beauty” but if he was, it was the only thing he was enslaved to. Day was born a wealthy Boston Brahmin and lived a life of wide choices and free thinking. The mild reticence expected of Bostonians of his class was mostly ignored by Day in favor of the personal expression that made his work seem scandalous then and groundbreaking now. Still, he kept his sexuality to himself. Day may not have wanted to make the same mistake his idol, Oscar Wilde, had made, the one that ultimately cost the playwright’s life.

Fred’s father, Lewis Day, a prominent Brahmin businessman, owned cattle ranches and leather companies. Although he was successful, Lewis Day passed none of his interest in industry to his son. The senior Day was often called away to tend his business enterprises, allowing Fred’s devoted mother, Anna, to raise him. When he was around Fred, Lewis Day was supportive and warm. As the only child, he received all of his parent’s attention. While some historians have called his mother “domineering,” others took note of her unusually progressive attitudes towards immigrants and African-Americans, which she passed on to her son. Anna took the democratic teachings of her Universalist faith seriously and her son inherited her world-view to great effect in his later work.

The Day’s home in Norwood, 23 miles southwest of Boston, was the center of their lives and always a touchstone for Fred. The family had an apartment on Boylston Street in Boston and Fred would later have studios there and in London but Norwood was always home.

In 1879, Fred’s mother, Anna became sick and was ordered to travel to Denver to recover in the fresh mountain air. Fred, a teenager, accompanied her. In Denver, he met Americans who were Asian and Latino for the first time, broadening his perspective. He purchased Chinese painting supplies and became fascinated by Asian-American art, which became a lifelong passion.

With his mother recovered, Fred returned to Boston, where he enrolled in the Chauncy Hall School (then located in Boston, now called Chapel Hill-Chauncy Hall School in Waltham). Fred was popular and his love of art and the artistic life was tolerated among his fellow upper-class peers. In his senior year, he embarked with fellow students on a European tour which included England, Ireland, Switzerland, Italy and France. He sent articles on his travels back home to the Norwood Review. Upon graduation, Day won a gold medal for best scholarship in English literature. This would be the end of his formal education.

Instead of following most of his friends to Harvard, Day took a desk job in a book publishing company at the urging of his father, who thought his son’s high-flung artistic interests needed leveling. The working world did not alter Fred’s love of art or beauty but he did put the experience to good use when he later founded his own publishing house, Copeland and Day.

At 22, Day began taking photographs, mostly of the homes of local authors, thereby combining his two passions: books and photography. His early pictures were taken in dim gaslight which required his subjects to hold their poses for long stretches. The availability of electric light was not widespread until after World War I but wealthy families began using electricity for lighting as early as the 1890s. The evolution in lighting from gas to electricity influenced Day and other early photographers, opening the way to Pictorialism, which created satiny, dark, photographs.

When Day was 22 in 1886, he met Louise Guiney, who would quickly become his closest friend. They shared a love of literature and art, especially the poetry of John Keats. Though he published just 54 poems in his short life, Keats was a beacon to young romantics like Day and Guiney even though he had died 70 years before. Day and Guiney were part of the fin-de-siècle generation who reacted against the growth of sprawling, impersonal, cities, unchecked capitalism, and the bulldozing of forests. They wanted to reclaim what they saw as a more spiritual past when the accrual of money was the not main object of life. Over time, Day’s less orthodox religious outlook allowed him to experiment with art photography in ways Louise Guiney, a staunch Roman Catholic, could not always accept. An example of Day’s lighter attitude towards religion was a plaque he mounted over a door to his Beacon Hill apartment: ”This is the Day the Lord Hath Made.”

Another pivotal relationship in Day’s life was his friendship and business partnership with Herbert Copeland, described by Jussim as “a well-educated, debonair, sophisticated young bachelor,” though other accounts mark him as ineffectual and a drunk. They shared an interest in books and art. But there were marked differences, too. Copeland was probably not as smart as Day, nor as hard working. Still, their partnership created one of the most respected publishing houses at the time. Between 1893 and the year it folded in 1899, Copeland and Day published about a hundred books by authors that included Oscar Wilde, Aubrey Beardsley, and Robert Louis Stevenson.

Later, Copeland became an alcoholic, often borrowing money from Day. Like Day, Copeland was almost certainly gay. He had relationships with men that he called “intimate.” In a letter to Day, complaining about a relationship with a married man, Copeland wrote, “I was desperately taken with him at first sight, and deliberately laid myself out to catch him…before I knew he was married.”

Day was famous for befriending young men from the slums of Boston. The most famous of these was poet Kahlil Gibran. He was generous financially and by all accounts, treated Gibran well. Another young man Day met was an Italian immigrant living in Chelsea whom Day used in his photograph, St. Sebastian. The boy was well aware of his good looks and the effect they had on both Day and his old friend Herbert Copeland who also knew him. When Copeland visited him, the boy’s mother, who did not approve of her son posing for the men said icily, “It’s very good of you Mr. Copeland to take such an interest in (my son).” The boy interrupted saying, “Nobody can help taking an interest in me, can they Mr. Copeland?”

In The Seven Last Words of Christ, Day uses himself as the model of a crucified Jesus with “Roman soldiers” looking on from below. He starved himself over several months to look the part. He purchased garments that matched those from the period. Even his father, on business in Florida, promised to buy large nails for the cross, if he could find them.

It’s difficult to know how to take the image. Is it a reverential reenactment of one of the most sacred moments in Christianity? Or is it an attempt at an homo-eroticized version of a central event in a religion that had condemned queer people? One suspects it is a little of both. Adrienne Lundgren, a senior photograph conservator in the Conservation Division of the Library of Congress, thinks it is not a reenactment of the crucifixion of Christ but a kind of performance art intended to elicit a response from the viewer. In short, it is art, not history or religion.

The New York pioneering art photographer, gallery owner, and art critic, Alfred Stieglitz, began noticing Day’s photographic work in the middle 1890s. Steiglitz had founded The Camera Club and turned its newsletter, Camera Notes into the most influential publication on photography at that time. In some ways, Camera Notes took the place of the old art academies that dictated which artist’s works would be selected or left out of annual shows. If your work was in Camera Notes, you were good. In 1903, Camera Notes evolved into a full-fledged magazine called Camera Work, which was the authority on photography until it folded in 1917. Both Stieglitz and Day were proponents of photography as art. But Day was not as interested in following the methods of great painters as was the New York group of photographers that surrounded Stieglitz. When Stieglitz copied Cubist painters by making Cubist photographs, Day ignored it.

Perhaps it is inevitable that Stieglitz and Day would become competitors. When Day felt shut out by Stieglitz, he responded in kind with icy silence. This would prove costly. When Day refused to have his work featured in the first issue of Camera Work, it spelled the end of their relationship and may have been the worst professional move of Day’s life. He could not have known the status that Camera Work would earn through the years as the arbiter of great Pictorialist work. This is the major reason why Day is too little remembered today. As Priscilla Frank pointed out in a 2012 Huffington Post article, before artists Cindy Sherman’s multiple personalities or Robert Mapplethorpe’s homoerotic images, there was Fred Day. It is long since time to base the position of Day’s work on more than his exclusion from one journal over 100 years ago.

By 1925, both of Fred’s parents and his close friends, Louise Guiney and Herbert Copeland had died. Now, Day spent long stretches of time upstairs in his bedroom at the house in Norwood. His last years were spent in increasing seclusion. Fred Holland Day died at 69, on November 12, 1933.

Was Day a gay man? We can’t know for certain but most everything points to it. He was unmarried and aside from his chaste friendship with Louise Guiney, all of his important adult relationships were with men. He used attractive young men in his photographs and befriended young men from Boston’s slums throughout his life. We know that his business partner, Herbert Copeland shared his interest in young men. His literary heroes were Oscar Wilde and Honoré de Balzac. The former carried on a public affair with a young man which was his ruin and the latter included gay characters in his realist fiction.

The 1890s were not a time for public pronouncements on sexual desire. But that didn’t mean Day was without desire. Maybe it was better, more artistic, to remain silent. After all, his hero John Keats, wrote: “Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard are sweeter…”

Well done..

Thank you.