The ’50s are a strange period– so bland and conservative on the surface, but with a lot bubbling up as well that would emerge in the turbulence of the 1960s.

–Neil Miller, author, Sex-Crime Panic: A Journey to the Paranoid Heart of the 1950s

Article published in Boston Spirit Magazine September/October 2014

It was a warm day for a cold war. The temperature reached 48 degrees in Wheeling, West Virginia, on February 20, 1950. Senator Joseph McCarthy (R-WI) strode onto the stage with the down home confidence that endeared him to regular folks. To his audience, the barrel-chested former Marine was a welcome contrast to the effete Washington politicians with their East Coast superiority and secretive ways. The members of the Women’s Republican Club of Wheeling were rapt as McCarthy dramatically claimed to possess a list of Communists working in the State Department. Over the next few weeks, his list of names fluctuated between 10 and 57 Communists.

In the end, McCarthy never produced a single one, but the fearful, repressive atmosphere his accusations created, hung over the country for years. Reputations, careers, and lives were ruined.

Labeled, “The McCarthy Era,” this period is a staple of high school textbooks as an object lesson in governmental persecution. Much less known was the mass interrogation and subsequent firings of thousands of gays and lesbians during this same period often called “The Lavender Scare.”

Within the federal government during the Cold War and extending into the 1970s, the assumption was that gays could be easily blackmailed by foreign agents who threatened to expose them as “sexual deviants” unless they provided secret information. Lesbians and gay men soon joined suspected Communists as the hunted. Unlike some of the accused movie stars and writers with leftist pasts, gays were easy targets because they could not retaliate. To complain to a newspaper reporter about forced interrogations and firings, meant admitting to being homosexual, something few people were prepared to do. By the end of the 1950s, over 5,000 federal workers were fired or forced to resign for being gay. Afterwards, some committed suicide, many others took lower-paying jobs in more accepting occupations like hairdressing and food service.

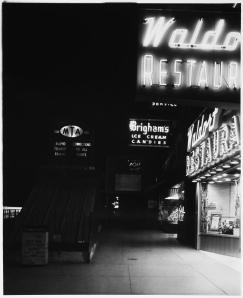

In the 1950s, the Waldorf Restaurant across from Park Street Station buzzed with gay people after the bars closed. Photo: Nishan Bichajian, Courtesy MIT Libnraries, Visual Collections.

The roundups soon spread to state and local governments and even to private companies. David K. Johnson writes in his book, The Lavender Scare, that a 1958 study estimated “one in every five employed adults in America had been given some form of loyalty or security screening.” But it was lesbians and gays who were singled out and fired. (The military continued to interrogate and fire LGBT people until the practice was outlawed on September 21, 2011.)

In the 1950s, suburban neighborhoods sprouted throughout the country, teeming with new families, who had fled the cities. The young medium of television portrayed heterosexual life as noble and natural, driving gays more underground then they were a decade before.

Given all of this, you would think 1950s gay life in Boston was a depressing combination of secrecy, loneliness, and self-loathing.

Except that it wasn’t.

Sure, it was risky and certainly underground. But for those who went to bars, nightclubs and restaurants that attracted a gay clientele, Boston gay nightlife was rich, varied and even glamorous.

With the exception of the late 1970s, the variety of gay nightlife during the McCarthy Era in Boston, has never been equaled.

Scollay Square still existed then, though its years were numbered. Located where Government Center is today, the area attracted gays to its bars, burlesque houses and theaters. John H. grew up just outside Boston in the 1950s, and recalls the burlesque houses as an introduction to Boston nightlife. “There was a group of gay guys in my high school who dropped out to move into town. We never said anything but we all knew they were gay. They took us to the old Howard and the Casino. It was dirty comedians followed by strippers. It wasn’t sexy for us but it was exciting. There was one stripper named “Countess Bareassity.” After the shows, we’d go to the bars.”

Boston was a more active port of call for sailors then and they where regular visitors to Scollay Square bars, especially the Lighthouse, Half Dollar, and Silver Dollar. Gay men and sailors could meet at one of these bars and take a room at one of the cheap, nearby hotels. And if you were down on your luck or too drink to go home, you could spend the night at the Rialto, a 24-hour movie theater where men met for sex.

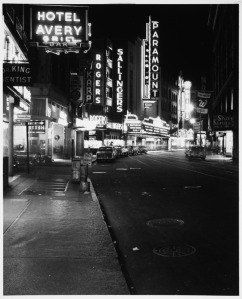

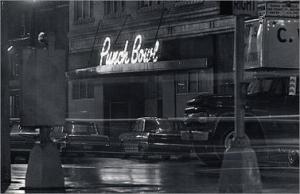

And then there was Park Square. The Punch Bowl, Jacques, the Napoleon Club, and Mario’s were all within a few blocks of each other. Unlike the Scollay Square bars that were ostensibly straight but frequented by gay people, these bars were expressly for gay people. The Punch Bowl was not hidden or at all secret. You could not miss the bold, cursive letters on it’s front: “The Punch Bowl.” In an interview with the Lesbian Herstory Archives, activist, Barbara Hoffman spoke about going to the Punch Bowl in the 1950s, “I still remember walking into this packed bar. It was an hour before closing, and they were six deep at the bar. I asked (my friend) Rodney if everyone here was gay, and he said yes. I couldn’t believe my eyes.”

Three blocks away, the Napoleon Club attracted a successful, older crowd. Liberace sometimes dropped by after a concert downtown. “The first gay bar I went to was probably was the Napoleon Club,” recalled the late Conrad Shumway in a 1995 interview with the History Project. “I think it was just one room downstairs (then) and a little entryway where you hung your coat. And of course, you had to wear a jacket and a necktie. The hatcheck girl, Ivory Rubin, would give you a beat-up old tie to put on. It would look like hell.“

Shumway had moved to Boston from Vermont in the early 1950s. One day, he walked into the Lincolnshire Hotel bar on Charles Street for a drink. “It was really a men’s bar for the hotel but the hotel’s business was fading away and it turned into a gay men’s bar. I met my partner there on June 27, 1952. He was in the real estate business.” Shumway and his partner ran boarding houses on Beacon Hill for the next 20 years.

Playland and the Chess Room were located in what later became the Combat Zone, Boston’s adult entertainment area in the 1960s- 1970s. The Chess Room served a dressy clientele of older men looking for younger men. It was in the basement of the Hotel Touraine. “The bartenders were hot as hell, but they didn’t like the gay clientele. To hold the job, they were told by the manager, ‘you’ve got to be nice to these people, they bring money in here. Behave.’ They wore white jackets with black bow ties, very proper. You had to wear a neck tie in there, too,” said Shumway.

Playland and 12 Carver Street attracted a more relaxed clientele. Blue-collar truck drivers mingled with Harvard students. Playland even had a few regular black patrons, unusual in Boston gay bars at this time. Phil Baionne, owner of 12 Carver Street (now replaced by the Transportation Building), was a large man who liked to mount a swing and glide over the crowd. Recalled Shumway, “He’d get all juiced up and get in his swing and say, “Now it’s time for Papa to swing. And she would sing “Summertime” and she’d wear a big straw picture hat with ribbons and bows and the ribbons hanging down and they would fly out and here she is, 300 pounds with this great big straw picture hat on… If she fell, she’d kill 300 people.”

After the bars closed, gay people went to the Waldorf Cafeteria and Childs — all-night eateries on Tremont and Boylston streets. Sometimes the noise level got so high the manger threw them out.

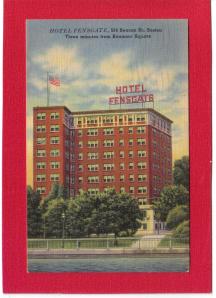

The highlight of the gay social season in the 1950s was the Beaux Arte Ball. The ball began in 1952 at the Fensgate Hotel at 534 Beacon Street, according to Shumway. The hotel manager was not happy when men waltzed into the lobby dressed in chiffon and ladies arrived in tuxedos. The ball moved to the Punch Bowl for several years where it attracted giant crowds, including many spectators who waited outside to see the men in drag enter in their lavish outfits.

One year, according to Shumway, a cab driver brought his wife to view the ball attendees. After the oohs and ahhs died down, he was heard to say to his wife, “Some of them look better than you. With that, she slapped him.”

The bleakest hours of the Lavender Scare of the 1950s have something in common with the height of the AIDS crisis of the 1980s. Under siege, queer people still danced and partied even as they were scapegoated, punished and neglected by their own government and society. For LGBT people, perhaps “the band plays on” because celebration is our gospel music. It defiantly proclaims: we’re still here.

would like to know if anybody remembers Jack Swann a piano player at 12 Carver in 74 – 75??? Like to know what ever hapened to him

I remember going to a gay bar called The Other Side. With a drag performer called Sylvia Sydney.. I didn’t find any mention of the place or her.. 1968-1971 ish

There seems to be next to no information about Phil Baionne (Bayonne?) on the Internet except for this fine article. Google has nothing. Yet, he was a major influence in Boston’s and Provincetown’s GBLT histories.